They served in the UN peacekeeping mission in Lebanon 40 years ago. 'I feel even more powerless now than I did then.'

Published on: October 13, 2024 ![]()

© Author: Kees Versteegh, Photos: Annabel Oosteweeghel.

The NRC newspaper spoke to five veterans who served in Lebanon in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

They discuss current events and look back on their time in the country. 'We can't leave those poor people to their fate. We have to do something.'

Jos Remmen remembers it well. Israeli tanks invaded Lebanon in the summer of 1982, and the then 23-year-old sergeant was supposed to stop the invasion, along with thousands of other soldiers from the then UN peacekeeping force. 'That was impossible,' says Remmen. 'Against those tanks there was nothing we could do.'

Jos Remmen remembers it well. Israeli tanks invaded Lebanon in the summer of 1982, and the then 23-year-old sergeant was supposed to stop the invasion, along with thousands of other soldiers from the then UN peacekeeping force. 'That was impossible,' says Remmen. 'Against those tanks there was nothing we could do.'

When the Merkava tanks reached a southern Lebanese village, the Israeli commander ordered all residents to put any weapons they had outside their houses. They had two hours to comply, or their homes would be destroyed

One family disobeyed the order and sought refuge. An Israeli tank rolled forward, and Remmen and the other UN soldiers watched helplessly as it obliterated the house.

Remmen recounts the story with the confidence of someone who lived it. Four other Lebanon veterans listen intently. The clink of glasses and laughter from other visitors to the café in Amersfoort is the only other sound. NRC asked the five men – all in their sixties – to come here to tell their stories about Lebanon then and now. They are here to give their views on current events. They will tell us who they see as the good guys and bad guys.

In 1978, the UN sent military forces to Lebanon after a bloody civil war and an invasion by Israeli troops. The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) had one clear objective: to maintain law and order, restore the authority of the Lebanese government and keep Israel out. Despite being intended as an interim peacekeeping force, the blue berets – named after the colours of the UN flag – are still engaged in that task 46 years later. Just late last week, it was reported that two 'Unifillers' were wounded in Nacoura after the Israeli army shelled a watchtower of the UN headquarters there. On Sunday morning, two Israeli tanks penetrated a UN base near Ramia, only to leave after 45 minutes.

The Netherlands was one of more than 40 countries that contributed soldiers to Unifil in 1979, including these five men. In 1985, this contribution largely ended. By then, nine thousand Dutch soldiers had been in the area. Nine soldiers died, twenty were wounded. Hundreds of veterans struggled afterwards with PTSD, depression and insomnia.

Injustice must be addressed.

The word "impotence" is mentioned several times during the group discussion in Amersfoort. It refers to the feeling of being unable to do anything when something shocking and unjust is happening right in front of you, as in Jos Remmen's case. The current batch of Unifil soldiers have to watch from behind the walls of their safe compounds, and it is infuriating. 'Even more than then, I feel powerless seeing the images now,' says veteran Bert Kleine Schaars, stirring his coffee.

At the same time, there is a sense of pride around the table. The men know they made something of it, despite the restrictions placed on the mission by 'politics'. These included relatively light armament and the rule that they could only shoot when they were being shot at.

At the same time, there is a sense of pride around the table. The men know they made something of it, despite the restrictions placed on the mission by 'politics'. These included relatively light armament and the rule that they could only shoot when they were being shot at.

'It was fantastic to see the area flourish when it was quiet for a while,' states Fred van der Ploeg, the technical specialist in 1979 responsible for towing away broken-down vehicles.

He is certain that the reason so many people are leaving the south now that Israel has returned is that, in the past, so many people moved there because of the relative calm.

I saw a lot of sad and anxious people then, and I see them again now.

When NRC points out that the Netherlands is no longer heavily involved in peacekeeping missions and is focused on defending its own territory, Van der Ploeg responds forcefully. "We have a responsibility to help those people in need, don't we?"

It was not a foregone conclusion that the five would accept NRC's invitation for an interview. Two other veterans declined, stating that it would all be too close again. Even among those who did accept the invitation, the stress was noticeable.

For one, there were tears.

Another has to 'smoke outside' more often than usual.

A fourth veteran, Herman Oorlog, ("Indeed, many jokes have been made about my name") states emphatically that today's television images hit him hard: 'I saw a lot of sad people and frightened people then, and I see them again now.'

They are filled with terror because they have no idea where the bombs are going to fall.

But all five are pleased to have the chance to discuss their past and current activities in Lebanon. 'It was intense,' Kleine Schaars states after the conversation.

World peace is possible.

'I'm doing something for world peace.' Bert Kleine Schaars had one clear goal when he volunteered to join the UN peacekeeping mission in Lebanon at the age of 19: to contribute to world peace. Little did he know. 'I had never left the Netherlands. But I thought: if I have to serve anyway, I'll make the most of it.' Besides, a term like 'peace mission', which the UN and Dutch politicians were always cautious about, had something to it. You could present it to your friends. 'In those days, it was frowned upon if you entered the army, even as a conscript. It was the time of the mass demonstrations against nuclear weapons.'

'I'm doing something for world peace.' Bert Kleine Schaars had one clear goal when he volunteered to join the UN peacekeeping mission in Lebanon at the age of 19: to contribute to world peace. Little did he know. 'I had never left the Netherlands. But I thought: if I have to serve anyway, I'll make the most of it.' Besides, a term like 'peace mission', which the UN and Dutch politicians were always cautious about, had something to it. You could present it to your friends. 'In those days, it was frowned upon if you entered the army, even as a conscript. It was the time of the mass demonstrations against nuclear weapons.'

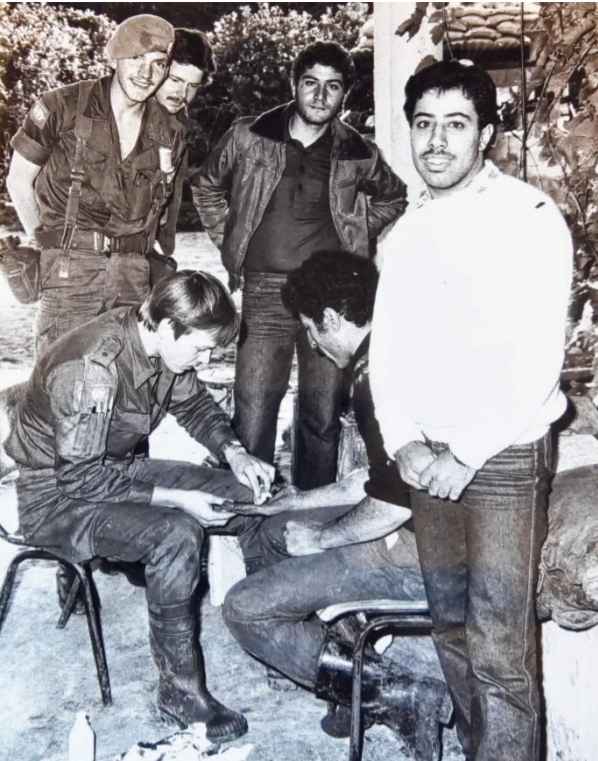

In 1978, Unifil was established during the bloody civil war that had gripped Lebanon from 1975. The UN peacekeeping force was there to prevent Palestinian fighters from the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organisation) and other militants from filling the gap after Israel withdrew from the south of the country. In an area sometimes difficult to access, Kleine Schaars and other 'blue berets' conducted their patrols. During the day, there were 'social patrols', as they were called. 'We were visible to the population. We talked to the villagers so they started warning us about PLO ambushes,' Jos Remmen states.

I had never left the Netherlands. But I was determined to make the most of my service.

At night, military patrols were riskier than during the day. Tunnel systems were not encountered, as they are now with Hezbollah. However, PLO militants did hide in deep cave vaults in the rocky landscape. 'In those caves we threw tear gas grenades to make sure no one was inside,' says Kleine Schaars.

He and other UN soldiers regularly encountered groups of Palestinians. They picked up the armed elements, disarmed them and took them to the nearest Unifil post. However, this was of little use as, already the next day, senior representatives of Unifil and the PLO came to that same headquarters to take back the confiscated weapons as well as the arrested men. Kleine Schaars stated, 'You just ran into those arrested Palestinians again on your patrols a little later.'

What are we doing here?

What should have been six months of fairly relaxed deployment for world peace turned into a stay from which the Unifillers increasingly asked themselves: what are we actually doing here? But then there was always the request for help from locals – bandaging a wounded cousin of a villager, repairing a broken shed – that still gave meaning to the work. 'Our main contribution was humanitarian, not military,' states Fred van der Ploeg.

Existing judgements of right and wrong were challenged. 'At the time, I had inherited a positive image of Israel from home,' says Kleine Schaar. 'It was a country you had to show solidarity with after the Holocaust. That image was severely tested in Lebanon.' Not only was the Israeli army the overlord who could, to put it mildly, act harshly against the local population, but there also appeared to be many Israelis who understood and spoke Dutch. This gave the Dutch Unifillers an uneasy, sometimes even unsafe feeling.

Our main contribution was humanitarian, not military

'They could listen in on our radio traffic,' Sergeant Kleine Schaars recounts. 'Our commanders warned us about that. If we were chasing the armed elements in our area and got into trouble, in no time you had even more trouble because the Israelis knew what was happening with us. They then also started shooting.' Sergeant Jos Remmen also had to adjust his image. Immediately after the Merkava tank shot the house to rubble, he told his soldiers, 'I said something very bad about Israel.'

There are good guys and bad guys.

There is a moment of silence at the table. And the room falls silent when NRC presents a statement by Commander Thom Karremans. The lieutenant colonel was the commander of the Dutchbat battalion that was tasked with guarding the 'safe' Bosnian Muslim enclave in and around Srebrenica in 1995. However, he withdrew in the summer under heavy Serbian pressure. The Serbs killed more than eight thousand Muslim men soon after. Karremans stated emphatically after Dutchbat's safe arrival in Zagreb that there were 'no good guys or bad guys' in the Bosnian Serb conflict. This caused quite a stir.

Nobody in the café in Amersfoort agrees with Karremans. "There were only bad guys in Lebanon, who were each other's enemies," says Fred van der Ploeg. Charles Borst, then a 19-year-old conscript sergeant in Lebanon, adds: "The good guys were just the innocent civilians who keep falling victim to wars."

Nobody in the café in Amersfoort agrees with Karremans. "There were only bad guys in Lebanon, who were each other's enemies," says Fred van der Ploeg. Charles Borst, then a 19-year-old conscript sergeant in Lebanon, adds: "The good guys were just the innocent civilians who keep falling victim to wars."

I have since been able to place everything in its proper context.

In the conversation about right and wrong, politics is also frequently mentioned, which sets the frameworks and conditions for missions. The five men are adamant that no progress is being made. 'Politicians still don't understand what you do to soldiers with a bad mandate,' says Bert Kleine Schaars. 'Look, for example, at what Macron said recently, nota bene the French president. He called for a ceasefire, based on UN resolution 1701. Doesn't he know that that resolution has been around since 2006 and has never been taken seriously?'

The conversation inevitably turns to Unifil in 2024. What can it still do? The answer is nothing. That's the general verdict. Kleine Schaars: 'The big difference with back then: we were still getting out and at least we were still patrolling, keeping an eye on things. Now the 1,200 Chinese taking part are mainly in their compound.' Jos Remmen nods: 'It's a kind of barracks they hardly ever get out of.'

The latest UN assessment report, published in February, revealed that the military had failed to inspect a single one of Hezbollah's approximately three thousand weapons depots. However, the Chinese contingent received high praise from the UN. In June of this year, the battalion was presented with a UN award in recognition of its exemplary contribution to local environmental initiatives in line with the UN's conservation principles.

Evacuate

The five men from Amersfoort follow events in Lebanon and Unifil's operations on a daily basis. Herman Oorlog, active on social media, 'often gets videos forwarded from families we met there at the time. On those, I recognise many of the places being attacked now.' Charles Borst can look at it relatively calmly. 'I have been able to give everything a good place in my mind by now.'

They know they were lucky. They did not experience truly traumatic events in Lebanon that would have permanently altered their lives. If they did, they were able to cope with them reasonably well. They had to do that on their own. There was no veteran care in Ministry of Defence back then. About 15 years after their time in Lebanon, sometime in the 1990s, the five men received a form from the Ministry of Defence with questions about their well-being. Jos Remmen is still angry about it. 'At question 4, I wrote on the form at the time: this is all a lie, because you won't do a damn thing with this anyway.'

Crying

Some in the group, such as Charles Borst and Herman Oorlog, continued to see each other through their work.

Some in the group, such as Charles Borst and Herman Oorlog, continued to see each other through their work.

Others, like Bert Kleine Schaars, now active in Deventer municipal politics, among other things, connected with them after the first Veterans Days that the Ministry of Defence started organising from 2005.

There were get-togethers and reunions. A few years ago, Kleine Schaars took the initiative to set up the Veterans for Lebanon Foundation.

That foundation delivered much-needed relief supplies to Beirut and its surroundings following the catastrophic explosion in the Lebanese capital's port in August 2020.

Some veterans even made 'return trips' to the area. Many of them came back purified. Herman Oorlog says, 'During my trip in 2018, our bus was pulled off the road by the police. We had to go with them to visit a nearby family.'

People and children came to us with photos of us at the time. They had kept them all this time. A little old lady in her nineties told us that we had saved her life and the lives of her children. We all had a good cry.

Source; NRC